Melanie Veasey | SCULPTURE SCRIPT

Melanie Veasey | SCULPTURE SCRIPTShe uses the materials of our troubled era to create work that is resolutely, and resonantly, of our time.[1]

Courtyard Sculpture

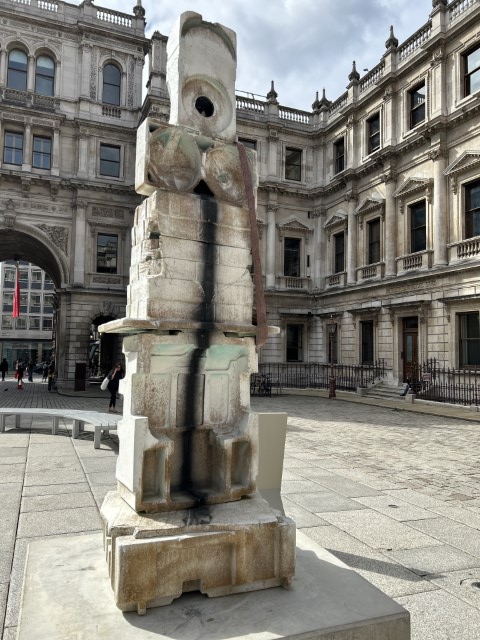

Each year a sculpture is placed in the Annenburg Courtyard heralding the Royal Academy of Arts’ Summer Exhibition.[2] This year, 2023, Huma Bhabha’s Ghost of Humankindness (2011), may perhaps be inadvertently overlooked through elegantly blending into this capacious greige location.

The sculpture stands offset before Alfred Drury’s garlanded, lofty statue of Sir Joshua Reynolds, who was the first President of the Royal Academy founded in 1768.[3] As a sculptor, Drury was ‘always in search of the graceful, the tender, the placid and the harmonious’.[4] Bhabha’s disconcerting characterisations, emulating dystopian worlds are in dramatic contrast to Drury’s tradition.

Melanie Veasey | SCULPTURE SCRIPT

Melanie Veasey | SCULPTURE SCRIPTAs Stranger

Mythologically, the title Ghost of Human Kindness might be Theoxenia. The Greek concept of hospitality and ritualised friendships, of generosity, gifts and reciprocity. Xenos as stranger. An outsider’s status which Bhabha — who was born in Karachi, Pakistan — experienced when she relocated to the United States, aged nineteen, in 1981.[5] Bhabha now lives and works in a converted firehouse in Poughkeepsie, New York.[6]

Portrait of Huma Bhabha © Time Out

A Kind of Rawness

Her myriad of fantastic composite creations are manifest in her international exhibits: ‘I’m interested in a certain kind of visceral aspect a kind of rawness in the work, which I like very much. It comes naturally to me’.[7]

Such hybridised beings were foregrounded by Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818),[8] and, a century later, fabricated in Jacob Epstein’s remarkable Rockdrill (1913) which fused ‘a machine-like robot, visored, menacing’, compelled the viewer to engage with the dystopian.[9]

Moreover, on 30 October 1938, American radio broadcast H. G. Wells’ alien fantasy War of the Worlds.[10] As fake news, Orson Welles adapted H. G. Wells’ forty-year-old novel into a production which terrorised the nation.[11] Since then America has been alert to potential space invasions and become enthralled to otherworldliness.

Themes of unspeakable terror, the monstrous, horror films and sci-fi spike Bhabha’s sculptures suffused by war, colonialism and displacement and the memory of home as “eternal concerns”.[12] Since 2012, the titles of her shows revealing the uniqueness of her figurative sculptures: ‘Facing Giants’; ‘Against Time’; ‘They Live’; ‘Other Forms of Life’; ‘We Come in Peace’; ‘Unnatural Histories’.[13]

The art historian, Eva Respini, identified the ‘intoxicating mix’ of Bhabha’s cultural references as ‘high and low, from ancient Gandhara, Alberto Giacometti, Greek kouroi, David Cronenburg films, Auguste Rodin, Constantin Brancusi photographs, comic books, Jason Bourne movies, Jean-Michel Basquiat, the writing of Arundhati Roy and Philip K. Dick, and Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines, to the television series South Park’.[14] Pablo Picasso[15] and Francis Bacon[16] were significant too as was Martin Kippenberger’s sculpture Untitled (1993) which inspired Bhabha’s direct response to his painted bronze as textured Styrofoam.[17]

The Ghost of Humankindness (2011)

As a work of ‘collage, montage and assemblage’,[18] the austere grey-whites of the Ghost of Humankindness evidence the griminess of sustained pollution, absent when the stark white painted bronze (from an edition of four) was originally installed at the Museum of Modern Art PS1, in Queens, New York.

Informed by her earlier constructs including: J. C. (2006); They Don’t Speak (2007) and Fear Eats the Soul (2007), a decaying putty-like flattened face has been overlayed, poked and prodded, the gouged eye sockets, flared nostrils and gaping mouth convey the immobility of stunned shock, resonant with Edvard Munch’s Scream (1893), just before the silence is pierced.[19]

Melanie Veasey | SCULPTURE SCRIPT

Melanie Veasey | SCULPTURE SCRIPTThe painted bronze emulates the tactile pattern of millions of compressed tiny foam bubbles imprinted from found industrial Styrofoam packing protection. Void spaces suggest their appropriated contents. The overhung horizontal intersection supports the brick stacked solid torso. Integral to the sculpture, scrunched upon this ledge rests an unfurling paper bag. Debris which fastidious Academy visitors mistakenly seek to remove in an indignant belief that someone had abandoned their lunch wrapper!

Melanie Veasey | SCULPTURE SCRIPT

Melanie Veasey | SCULPTURE SCRIPTAsymmetrically, a sinuous brown belt vertically girdles the figure’s right side. The left side banding is absent suggesting deformity. Towards the left side of the base a burry tree root formation is shielded within a cavity. At the back, a paint sprayed blackened spine divides the torso space, where spherical indents might suggest breasts for an otherwise ungendered persona.

Melanie Veasey | SCULPTURE SCRIPT

Melanie Veasey | SCULPTURE SCRIPTOf Our Time

The understated stance of Bhabha’s Ghost of Humankindness speaks to the unnoticed gesture, the necessity of improvisation and the wilful survival of a distressed society. Memorialising those who quietly arrive then simply merge into the community without calling attention to their successful integration.

Yet in thoughtfully juxtaposing Bhabha’s other worldly Ghost of Humankindness against Drury’s fêted statue of Joshua Reynolds, perhaps the Royal Academy also makes the bold statement: Look how far we have come!

Citations

[1] Respini, Eva. 2018. ‘Instant Ruins.’ in Respini Eva (ed.), Huma Bhabha They Live (The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston and Yale University Press: New Haven), 9-25. 25.

[2] https://academic.oup.com/astrogeo/article/44/2/2.20/278975, accessed 11 July 2023.

[3] Alfred Drury (1856–1944).

https://bowmansculpture.com/artists/115-alfred-drury/biography/, accessed 03 July 2023.

[4] https://bowmansculpture.com/artists/115-alfred-drury/biography/, accessed 03 July 2023.

[5] Huma Bhabha (1962–).

http://www.davidzwirner.com/artists/hua-bhabha/biography, accessed 03 July 2023.

[6] Medvedow, Jill. 2019. ‘Director’s Foreword.’ in Eva. Respini (ed.), Huma Bhabha They Live (The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston and Yale University Press: New Haven). 7.

[7] https://salon94.com/artists/huma-bhabha/ accessed 01 July 2023.

[8] Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797–1851).

[9] Sir Jacob Epstein KBE (1880–1959).

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/epstein-torso-in-metal-from-the-rock-drill-t00340,

accessed 05 July 2023.

[10] Herbert George Wells (1866–1946).

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/infamous-war-worlds-radio-broadcast-was-magnificent-fluke-180955180/, accessed 05 July 2023.

[11] Ibid. Orson Welles (1915–1985) and the producers ‘found the story too silly and improbable to ever be taken seriously … desperate attempts to make the show seem halfway believable succeeded, almost by accident, far beyond even their wildest expectations.’

[12] Respini, Eva. 2019. ‘Instant Ruins.’ in Respini Eva (ed.), Huma Bhabha They Live (The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston and Yale University Press: New Haven), 9-25.

[13] http://www.davidzwirner.com/artists/hua-bhabha/biography, accessed 03 July 2023.

[14] Respini, Eva. 2019. ‘Instant Ruins.’ in Respini Eva (ed.), Huma Bhabha They Live (The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston and Yale University Press: New Haven), 9-25.

[15] Pablo Picasso (1881–1973).

[16] Francis Bacon (1909–1992).

[17] Ruby, Sterling. 2019. ‘Huma Bhabha in Conversation with Sterling Ruby.’ in Eva. Respini (ed.), Huma Bhabha They Live (The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston and Yale University Press: New Haven). 187-191.

[18] Foster, Carter E. 2019. ‘Drawing Raw.’ in Eva. Respini (ed.), Huma Bhabha They Live (The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston and Yale University Press: New Haven). 33-41.

[19] Edvard Munch (1863–1944).